Beyond screen size: A deep dive into the technical exchange that instantly tells a web server what kind of device you're using, and the ways web publishers can abuse it

Let's talk about tech.

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Enjoy our content? Make sure to set Android Central as a preferred source in Google Search so you can stay up-to-date on the latest news, reviews, features, and more.

Welcome to Tech Talk, a weekly column about the things we use and how they work. We try to keep it simple here so everyone can understand how and why the gadget in your hand does what it does.

Things may become a little technical at times, as that's the nature of technology — it can be complex and intricate. Together we can break it all down and make it accessible, though!

How it works, explained in a way that everyone can understand. Your weekly look into what makes your gadgets tick.

You might not care how any of this stuff happens, and that's OK, too. Your tech gadgets are personal and should be fun. You never know though, you might just learn something ...

The User Agent String

A website can be many different things, but no matter what it's trying to show you, it has to be able to get the information from the internet to your screen. Getting it there is only half the battle, though, because once you've received it, the way it appears can make all the difference. We've all seen websites that have a different layout or format based on the device you're using (you're on one right now!), but what makes it work? Are you tagged and tracked across the internet so that everyone with a web presence knows whether you're using a phone or a laptop?

Thankfully, no. It's a complicated process made simple for the people building the browser by placing all the work on the web host, called a User Agent String.

Every bit of software capable of perusing the contents of a website has a UAS. The web browser you are using right now has one, AI content scrapers have one, and even some web browser extensions have one. They offer it to the web page when it's requested, so the web page knows what to send back.

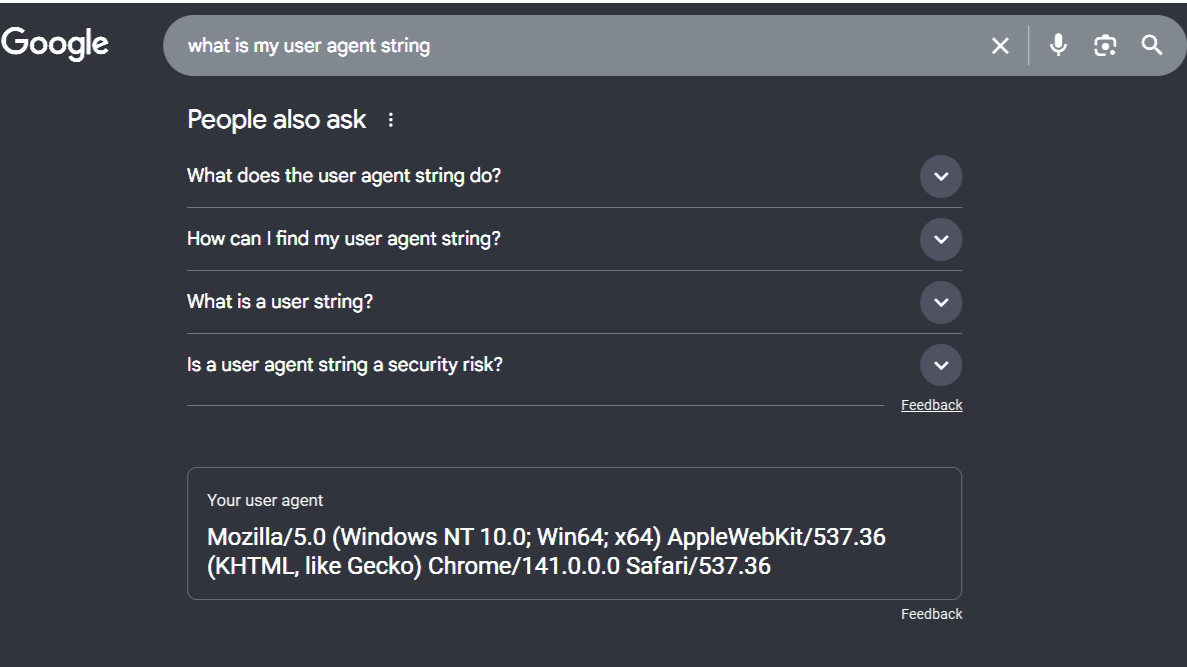

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/141.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

That's my own UAS as I'm writing this. You can find yours simply by opening Google Search and asking, "What is my user agent string?" and it will tell you because it asks your browser, and your browser tells it — the same process as any other website.

This, along with other information like screen dimension, the number of colors your graphics adapter and display can render, and any requested language support (this is also stored and kept ready to send if needed), is what turns a bunch of code into what you see once the browser on your device gets something it can use to create it. Yes, your web browser is building the website from internet addresses and strings of code.

This sounds awfully confusing, and it certainly can be. That's why the workload is somewhat divided. A web browser installed on a device, regardless of its type, has plenty to do when it receives the raw data to build something coherent out of. However, it must retrieve the correct data, as different browsers construct web pages in distinct ways.

A website has plenty to do, ensuring that different versions of the layout, image sizes, colors, and fonts are rendered correctly by your browser's engine, but it must know what to send.

The process:

A device like the phone in your hand visits a site on the internet by a complex (and a whole different article's worth of complications) series of routing until a connection between your browser and the web server is established.

The web server queries the browser, asking about the type of device, its capabilities, the display size, and the number of colors the device can render, among other details.

The web browser has this information readily available in a convenient and persistent manner. It sends a few lines of text back with minimal effort because it's already there, ready to go.

The web server takes this information and decides what version of the website to send back, and you get to see it.

Thankfully, the best part of the whole process is the fact that we don't have to do anything. We can click on a link and see what we were hoping to see. It's perfectly safe, has nothing to do with sending any sort of personal information or tracking you across the web, and it honestly does "just work."

Abusing the process

Unfortunately, this is easily abused by web publishers. I won't tell you how to change the UAS of your device because it's an easy way to break stuff, but it's not hard to do. A web server can't look through a hidden camera and verify that it's receiving the correct information, so it accepts what it's told. It has to, if anything is going to work.

You probably guessed that AI is involved in this abuse, because welcome to 2025. And it's somewhat disheartening to see what companies are doing; it has the potential to make a complicated process that has required a lot of work seamless and fast, and forcing it to change.

I'll use the most recent example I can think of, but we can assume that every company scraping the web for content to feed its AI does the same thing. Perplexity, a relatively new entrant to the AI scene, was caught experimenting with various UASs and disregarding requests about its capabilities, allowing it to "steal" content from websites and use it without any form of agreement.

Most websites have a policy about what an AI scraper can and can't use for free, and pretending to be something else allowed Perplexity's scraper to access things it wasn't supposed to access.

No matter how you feel about AI "stealing" content or web publishers, anything that could disrupt something that works so well is troubling. We'll see what, if anything, needs to change to prevent this sort of thing, but in the meantime, know that software is working hard to ensure that all you need to do is click or tap and see everything the web has to offer.

FAQ

What is the primary way a website detects the type of device I’m using?

The primary method for detecting your device type is by reading your User-Agent string. This is a small line of text that your web browser (such as Chrome, Safari, or Firefox) automatically sends to the website/web server with every request. It contains information about the browser you're using to view the site, the operating system, and the device you're using, so that it can render the correct version of the website suitable for your screen.

What kind of information can web servers receive about your device from the User-Agent string?

Screen resolution/Viewport size: By checking the height and width of your browser window, the website can infer if it's running on a small phone, a tablet, or a large desktop monitor. This is key to responsive design.

Touch Capabilities: Checking if the device has a touch screen can help distinguish between mobile and desktop devices.

Hardware and software capabilities: Less common methods include checking for specific browser APIs, CPU architecture, and other hardware details to further refine the device profile.

Can a website be wrong about the type of device or browser I’m using?

Yes, device detection is not always 100% accurate. Accuracy can be compromised for a few reasons:

Spoofing: Users can deliberately change (spoof) their User-Agent string to make the website believe they are using a different device or browser.

Outdated databases: Some websites rely on external databases to map a User-Agent string to a device. If these databases aren't updated, they may misidentify new devices.

Security/privacy tools: Some browser extensions or VPNs may obscure or modify the data sent to the website.

Why is it important for a website to know what device I’m on?

A website needs this information to deliver the best user experience possible. This is primarily for:

Responsive design: To display the correct layout, image sizes, and navigation menu optimized for your screen size (e.g., stacking content vertically on a phone vs. horizontally on a desktop).

Feature management: To decide whether to offer certain features, such as deep linking to a mobile app store or a desktop-only feature that requires a mouse and keyboard.

Jerry is an amateur woodworker and struggling shade tree mechanic. There's nothing he can't take apart, but many things he can't reassemble. You'll find him writing and speaking his loud opinion on Android Central and occasionally on Threads.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.