The mobile photography revolution - Talk Mobile

Presented by BlackBerry

Talk Mobile Creativity

The mobile photography revolution

The camera. If there's any part of the smartphone that's seen its usage rate skyrocket over the past few years, that'd be it. Smartphone cameras have gone from little VGA shooters barely worthy of being called a camera to 12, 20, and even 41 megapixel beasts with image quality unfathomable just a few short years ago.

We now walk almost everywhere with a small camera in our pockets or purses, logged in to Facebook and Instagram and Twitter, ready to share our latest heartwarming, heartbreaking, intense, intriguing, and inane moments with our family, our friends, and the world.

So are mobile phone cameras really good enough to replace a dedicated point-and-shoot camera? What about a bigger traditional DSLR? With these photos ever easier to share and reshare, how can we be sure that the photos we take that need to be private stay private?

Let's get the conversation started!

by Rene Ritchie, Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, and Phil Nickinson

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Photography

Articles navigation

- Point-and-shoot cameras

- Video: Derek Kessler

- DSLRs

- Video: Simon Sage

- Photo privacy

- Photo backups

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Smartphones killed the point-and-shoot star

That place reserved for the point-and-shoot doesn't exist anymore. It's been crowded out from the bottom by ever improving smartphone cameras, and from the top by more accessible and affordable interchangeable lens cameras. The point-and-shoot can't take photos well enough to compete with the big cameras, and it's not portable or flexible enough to go toe-to-toe with modern smartphones.

The point-and-shoot can't take photos well enough to compete with the big cameras, and it's not portable or flexible enough to go toe-to-toe with modern smartphones.

Point-and-shoot cameras aren't gone - new ones get announced all the time - but their reason for being is mostly legacy. It's not unlike the years that it took for Palm to get rid of aerial antennas. They had the technology to be rid of them for years, but consumers for whatever reason thought they still needed them. So they kept making them.

That's not to say that point-and-shoots are bad cameras. They have bigger sensors, more flexible optics, and are getting cheaper by the day (partly due to the aforementioned crowding-out). But why spend the money on a cheap point-and-shoot when you're already carrying a smartphone with a camera that's going to be adequate for 95% of your shooting needs?

What are these "megapixels"?

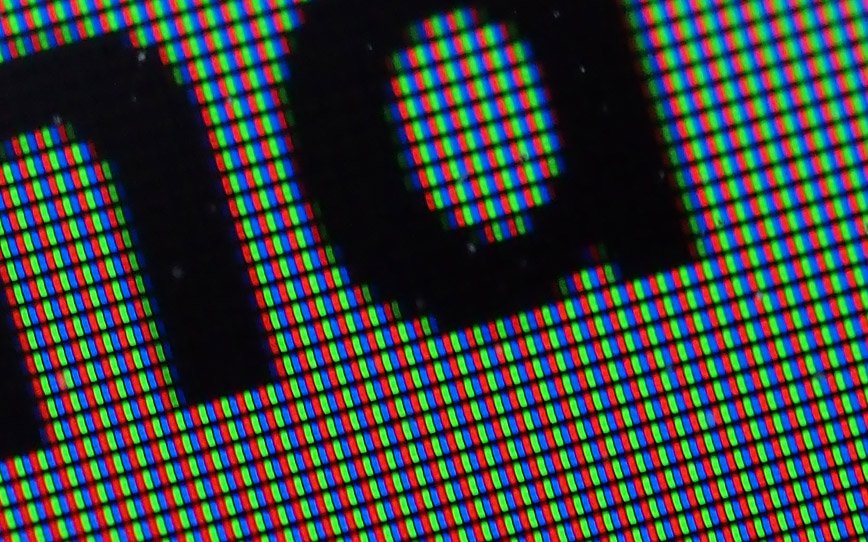

A "megapixel" is a number of pixels, specifically one million pixels. When you see a camera that's advertised as having 12.1 megapixels, in reality it has 12,100,000 individual pixels, or something close to that number.

As every camera a grid of sensing pixels (matching the grid of glowing pixels that is the screen), the pixel count can be found merely by multiplying the number of pixel rows by the columns. A sensor that measures 3,264 horizontal pixels by 2,448 vertical pixels would produce an image with 7,990,272 pixels, which would typically be advertised as a round 8.0 megapixels.

What is a point-and-shoot going to do that your smartphone can't? Just think about all the things that your smartphone can do with its photos that a point-and-shoot can't, or at least can't do easily. Ever try uploading a photo to Twitter or Instagram from a point-and-shoot, or cropping and performing color correction, or putting it into an app that distorts you to look fat?

Smartphones are pushing further and further into point-and-shoot territory. They're getting more advanced optics, better stabilization, and even more megapixels. Hell, Samsung just grafted a 16 megapixel 10x zoom point-and-shoot onto a Galaxy S4. Nokia's Lumia 1020 has an absurd 41 megapixel sensor for digital zoom that doesn't result in a blurry pixelated disappointment. And Sony just announced a pair of clip-on sensor/lens combos for iPhone and Android smartphones that gift high-quality imaging to otherwise okay-to-good cameras.

While some may mourn the death of the point-and-shoot (especially the imaging companies for whom they were cash cows), it simply ran out of reason for being.

Smartphone cameras may not be better cameras than point-and-shoots, but they're better for us.

- Derek Kessler / Managing Editor, Mobile Nations

Is there still a place for point-and-shoot cameras?

876 comments

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

The physics of light, DSLRs, and smartphones

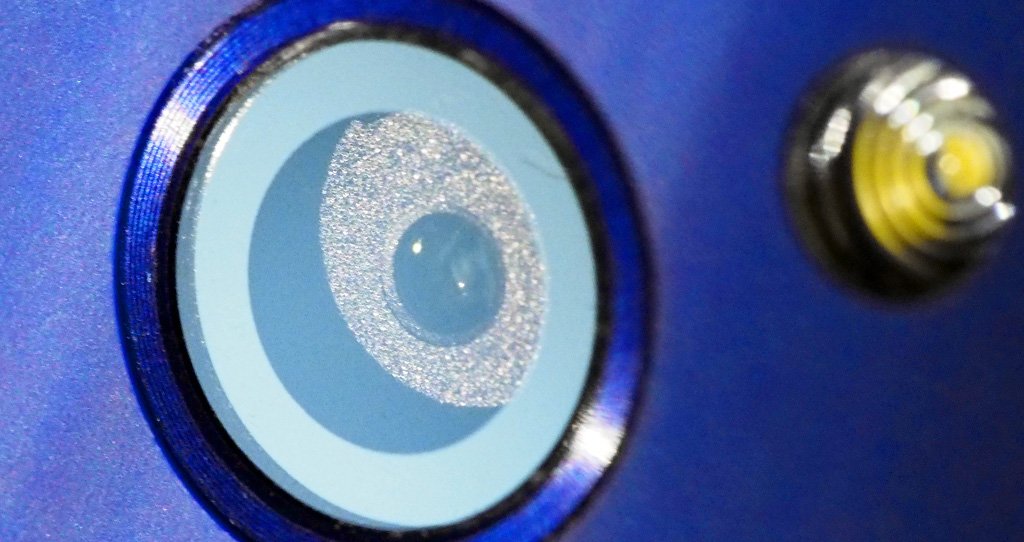

If you own a DSLR camera and have likewise invested thousands in lenses and associated equipment, chances are that giving up that bad boy for a smartphone are slim. What makes a DSLR a DSLR is the large sensor and interchangeable lenses, something with which tiny cameras cannot compete.

But does a smartphone need to replace a DSLR? In just the first half of 2013, we saw three interesting advancements in mobile photography: HTC's One camera with a focus on pixel size instead of megapixels; Samsung's Galaxy S4 Zoom with a large mechanical zoom lens and Nokia's Lumia 1020 with a massive 41 megapixel sensor. All represent different solutions to various problems within mobile photography and all show that traditional digital photography is up for a change.

Professional photographers won't give up their DSLRs. They're just too good at what they do.

Professional photographers won't give up their DSLRs and prime lenses though anytime soon. They're just too good at what they do, and with a slow but steady drop in price and increase in quality they're becoming more accessible. Point-and-shoot cameras though are on notice. Eventually categories will be redefined where users have an all-in-one smartphone with a robust camera and they optionally have a high end "real" camera for "serious" photography.

Traditional digital photography is under threat from that magic word again: social. Printing photos is very passé in 2013. Right now, it's all about sharing. Facebook. Twitter. Instagram. You name it and people are posting pictures to it and that is why mobile photography is so huge. Going home, loading them on the PC, putting them through and editor and posting to Flickr? Ain't nobody got time for dat!

Digital single-lens reflex

The DSLR - digital single-lens reflex - camera is for most photographers the pinnacle of camera technology. With large sensors, heavy-duty mechanical stabilization, manual controls, a slew of physical buttons, and a wide array of swappable lenses, the DSLR is more powerful and, optically-speaking, more flexible than point-and-shoot or smartphone cameras could ever hope to be.

Most DSLRs use a mirror to direct light directly from the lens to an optical viewfinder. This lets the photographer see the subject almost precisely how it will be be shot, unlike with a point-and-shoot which might have an inaccurate optical rangefinder (an offset peephole with optics that approximate what the sensor sees) and the point-and-shoot and smartphone with their screen-based viewfinders that pull data directly from the sensor. When a DSLR's shutter button is pressed, in addition to the shutter opening the mirror flips up and out of the way so light can reach the sensor.

A new breed of smaller interchangeable lens cameras, including Sony's NEX cameras and the Micro Four Thirds system developed by Olympus and Panasonic, have scaled down the size of the typically bulky DSLR with smaller sensors and by doing away with the mirror. In doing so, they've also abandoned optical viewfinders, though some do sport electronic replacements.

There's nothing quite liking documenting a live concert, a political riot, your cat rolling on the couch, or what you're imbibing for that evening when you and your friends paint the town, in real time. The ability to quickly share photos is something that a DSLR or even most point-and-shoots can't do.

With Nokia's Lumia 1020, for the first time, mobile digital photography is getting good enough to leave your dedicated camera at home. We say "good enough" because the image quality is still not there yet, but for all intents and purposes, it doesn't matter. DSLRs won't go away as professionals will always desire them, but their market will shrink as mobile photography grows to match the technology. The revolution will be posted to Facebook.

Over time I think we're going to see a lot of people ditching their DSLRs for smartphones

- Simon Sage / Editor-at-Large, Mobile Nations

Who makes the best smartphone cameras?

876 comments

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Before you take that picture…

I have a rule. If it's a picture I never want someone to see — whether it's of me or someone else — I don't take the picture. (OK, I know I shouldn't take the picture. Having the willpower to point the lens away from my attractive wife is another story altogether.) The first and best control over mobile pics that perhaps don't need to be seen by everyone comes from you, the photographer. Take your finger off the shutter button, point the lens elsewhere, and just store the image with your eyes and brain.

But that's boring. Of course you're going to take pictures. And of course you're going to — on occasion, perhaps on purpose, perhaps not — take pictures that should remain private. Or at least semi-private. What you do with your photos between yourself and consenting partners is your own business.

The moment the picture leaves your phone, it leaves your control.

The simple fact, however, is that the moment the picture leaves your phone, it leaves your control. You now have zero guarantee that said snapshot won't end up someplace it shouldn't, and 100 percent certainty that you'll be held responsible if it does. Especially if it's not a picture of you. There is no true privacy in sharing — only the illusion of privacy.

Backside illumination

A traditional digital camera sensor is constructed of a grid of sensing pixels, each with a lens on top, followed by wiring, and then the actual photodetectors. This arrangement is simple and easy to produce, and has been in manufacturing for decades. Having the wiring between the lens and the sensor, however, means that some of the light that is reflected back and never reaches the sensor.

Backside illumination flips things around, most literally. The photodetector and wiring silicon is flipped such that the back side of is facing the lens. The silicon wafer is shaved down thin enough that light can pass through and hit the photodetector, unobstructed by the wiring. Backside illumination is said to increase exposure by 60-90%. The process does result in a more expensive, harder to manufacturer, and fragile sensor chip.

You're still going to take and share pictures you shouldn't, aren't you? Fine.

You need to know where you're sharing them, and this can vary greatly from app to app. Perhaps it's binary. Either everyone can see your stuff, or no one can see your stuff. Apps like Facebook are a little more nuanced. Maybe only your friends can see your pictures. Or maybe it's friends of friends. Or friends of friends of friends. Or roommates of friends of friends. Sharing on Google+ lets you share to specific "circles" of friends. Snapchat lets you send self-destructing photos (though they can be saved with a simple screenshot). And so on and so forth.

It's up to you to know the rules of the road for the networks you're using. Exercise some common sense, think about who is potentially going to see this photo, and only then consider even taking it.

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile creativity

Rene Ritchie iMore

To the cloud! Backing up mobile photos

I suck at backing up photos. I typically shoot what I need, move it over to Aperture on my Mac, edit it in Photoshop, save it out, share it either on iMore or via Dropbox link to my friends and family, and then delete it forever. Which is, frankly, stupid.

I can't count the times I've gone back and wished I could get at the original image again. Be it to get a new size or aspect ratio - we recently switched from standard 16x9 to Retina 4x3 on iMore - or to share with people I hadn't already shared with. And I can't. Because, stupid.

Stabilization

Lens stabilization uses a system of either electromagnets or springs paired with gyroscopic sensors to compensate for movement of the camera by shifting the lens elements over the sensor. These systems can only compensate for linear movement perpendicular to the camera. While a lens stabilization could technically include rotational stabilization, doing so would be futile.

Sensor stabilization uses gyroscope data to instead move the sensor to compensate for the movement. The same elements are used to stabilize the sensor, along with actuators to rotate the sensor as needed to compensate for rotational agitation.

Digital stabilization is primarily only useful in video applications. When recording with digital stabilization the sensor is oversampled, meaning pixels outside of the bounds of the video are active and are used as a digital buffer using gyroscopic data. Post process stabilization analyzes the video for shake and crops the video to compensate for the moved frames.

In honor of Talk Mobile, and in shame of being so negligent, I've switched to a new process. Apple, bless their patronizing hearts, has made Photostream so everything I shoot on my iPhone gets automagically uploaded to iCloud, kept for 30 days online and on my device, and forever on my Mac. My Mac Pro gets cloned every night to a bootable backup drive, thanks to SuperDuper!, and my MacBook Pro gets incrementally backed up over the air to a Time Capsule. It's not bulletproof, but it's good enough for me at this point.

You need one or more local backups and one or more cloud backups.

Photos that I take with my DSLR, a big honking Canon, get pulled into Aperture. There, I still insta-delete the 90% of them that suck, but the ones that don't suck now get stored and backed up, same as the Photostream mobile photos. Again, not perfect, but good enough.

It's not the specifics that matter, however. It's the idea of one or more local backups and one or more cloud backups. Instead of or in addition to Photostream you could easily use Dropbox, Google+, or Skydrive (Facebook scales stuff down, so it's not a good choice). Any of my really important photos are also on Dropbox (as is my entire Documents directory). Dropbox syncs as a local folder on my Mac, so that too gets backed up to the SuperDuper! clone and the Time Capsule.

As long as it's on more than one drive, so if one fails you can still get to it, and in more than one place, so as long as one burns to the ground you can still get to it at another, you're in good shape.

How do you backup your photos?

876 comments

Conclusion

Having a connected camera always within reach has changed how we share and how we remember. It's made it easy - perhaps too easy - to share our excitement, our anger, our wonder, and our intimate moments with those close to us and the world at large. These cameras have disrupted industries, broken news, brought down public figures, and enriched our lives - all because they're always on us, for better or worse.

Rapidly improving smartphone cameras combined with increasingly accessible DSLR beasts and a new smaller breed of interchangeable lens cameras have all but squeezed out the point-and-shoot's reason to exist. Even the DSLR has come under threat from the smartphone camera just by its sheer ubiquity and convenience. It'll never be possible to match the DSLR's quality in a smartphone thanks to the physics of light, but the smartphone is approaching "good enough" for many applications.

But once we have these cameras we need to be smart about how we use them. We have to remember that once we hit send or submit or upload and that photo leaves our phone that we've lost control of it - even if we were just sending it to one person. And with everything that we're documenting with our cameras these days, saving those photos to our computers and the cloud is more important than ever.

Smartphones have changed how we live, and the smartphone's little camera has played an important role in that.