Tech Talk: How does a tiny smartphone camera take such good photos?

Minature marvels.

Welcome to Tech Talk, a weekly column about the things we use and how they work. We try to keep it simple here so everyone can understand how and why the gadget in your hand does what it does.

Things may become a little technical at times, as that's the nature of technology — it can be complex and intricate. Together we can break it all down and make it accessible, though!

How it works, explained in a way that everyone can understand. Your weekly look into what makes your gadgets tick.

You might not care how any of this stuff happens, and that's OK, too. Your tech gadgets are personal and should be fun. You never know though, you might just learn something ...

What is this sorcery? This camera hardware should never take photos this well.

Unless you take photos for a living or as a serious hobby, chances are the camera on your phone is the best one you have. It didn't always used to be that way.

About 10 years ago, I tested a $12 Barbie-themed disposable camera against a few expensive smartphones, and that cheap camera that was designed to be thrown away once you've used it did a much better job. We've come a long way.

It still seems like magic, though. The camera on even the best phones has terrible hardware when compared to most any other camera. It lacks any focal depth, is built of plastic and not glass, and the sensor itself is just so tiny. You would expect the photos that come out of it to be terrible. But they aren't.

There are two reasons for it — one technical and one practical. I'm not going to dive really deep into the technical side, but here's a quick overview of how it all works.

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

The electronic shutter chain

Your phone camera is a lot like a camcorder or a webcam because a series of events happens that we call an electronic shutter. You might have seen people take a roll of film and use a tiny hole in cardboard to take a photo, but digital cameras — including the one on our phones — are a different beast.

Your camera's sensor is an array of light-sensitive electronic devices called photodiodes. The amount and intensity of light that hits each one decides the amount of bias current applied to each individual one.

That flow of electrons is sent to what's called a charge well, which is basically a storage capacitor, and you have one for every pixel (1 MP = one million pixels). As long as the bias current is present (meaning the camera is actively gathering light) the charge is collected until the charge well fills.

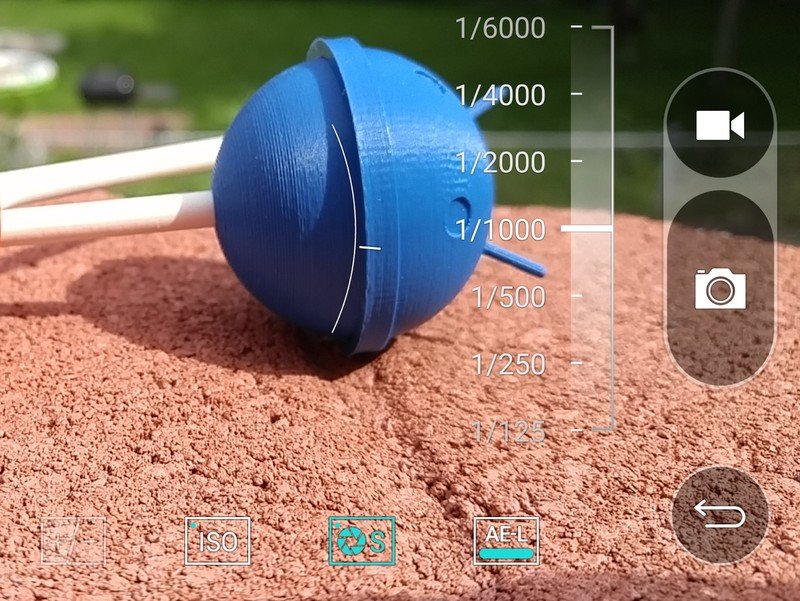

When it's time to turn this electricity into something else, the diode is turned off and the charge is converted into a specific voltage, then run through a filter and amplifier to "clean" up the signal, and into an analog to digital converter. This produces a 10-bit (or 12-bit or even 14-bit, depending on the sensor) number for each and every pixel. You can often choose the amount of time this shutter gathers data in your camera settings if you like to tinker.

All of this is called an electronic shutter. When you activate it, the charge wells fill with data, converted to a voltage, then a number, and can be read. This is a never-ending loop or stream of data that keeps happening until it's told to stop. It's the electronic equivalent of pushing the button on a "real" camera.

That data gets sent to specialized chips and software from companies like Google, Apple, or Qualcomm read and adjust those numbers to try and make a perfect arrangement of all the pixels of color. The software is a lot more important than the hardware because a stream of light information is constantly changing; capturing it perfectly doesn't matter as much as what you turn it into.

Of course, there are a lot of other details and methods, but this is the basic explanation of how a device with a sensor that's "always on" turns what's in front of it into a photograph.

The practical side

Electronics aside, the important reason why we love the pics our phones take is more practical: The source is matched to the destination.

That sounds like some sort of weird ancient philosopher gibberish, but it's true. A smartphone camera is designed to take photos that look really good when viewed on a screen, like the one on your phone. Since most photos are shared from one phone to another, or from a phone to a laptop or something else with a display, the photos look great. If you take your favorite photo to Walmart and have it printed out as a poster, you're going to hate it.

If you compare a smartphone camera photo with a photo taken from a camera with glass lenses, an adjustable aperture, and a larger sensor, you'll find they only look good when they're very small and the individual pixels are densely packed together. This is by design — the algorithms that turn the electrical noise into a photo I described above were tuned to do just this — make it look as good as it can on a small display.

Size matters here. A 16MP sensor on a phone is one-fortieth the size of a 16MP sensor on a DSLR camera, so there is 40 times more light data to work with on the professional camera. This is clearly evident on an unedited capture, but you'll never see one even if you take photos in your phone's RAW output mode. Software governs every step, and you don't get to control most of it.

What matters is what we see

What's really important is that you like the photos you can take with your phone, not how they are created. Phone makers have done a lot to improve the camera because it's a feature almost everyone loves and uses. They've done a good job.

When you take a picture of your kids or pets and send it off to your best friend, you can be pretty sure they'll appreciate it because it looks great instead of considering all the science and technology that went into making it.

Jerry is an amateur woodworker and struggling shade tree mechanic. There's nothing he can't take apart, but many things he can't reassemble. You'll find him writing and speaking his loud opinion on Android Central and occasionally on Threads.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.