Net neutrality is worth fighting for

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We tend not to branch out into the political discussion here at Mobile Nations all that often. Politics has little bearing on the day-to-day use of mobile devices. But on occasion, things from the political world cross into our little world of smartphones and tablets. Take SOPA back in 2012, for example. Meant to address the real problem of content piracy, SOPA overreached and the reaction of the American people was enough to kill the bill while still in committee.

We're facing another intersection of politics and technology today, and it's time that we the people made our voices heard. Net neutrality is the issue of the day, and the way that governments move on this issue will have far-reaching consequences for decades to come.

Just what is net neutrality?

In its simplest form, net neutrality is the principle that all traffic on the internet should be treated equally, without discrimination as to its source, destination, or content.

Net neutrality is the principle that all traffic on the internet should be treated equally, without discrimination as to its source, destination, or content.

That discrimination boils down in reality to the role of the service provider. For most of us, that's a hardwire internet service provider (ISP) for our home and work internet connections, as well as our cellular service provider for the internet connections on our mobile devices. These companies are the backbone of our internet connection, and for most they're our only viable connection to the internet.

That in and of itself is not a bad thing. Where things get bad is when these companies that manage the infrastructure of the internet attempt to use that infrastructure as a weapon to control the traffic on the internet.

The concept of net neutrality comes into the real world when ISPs, both landline and cellular, start to treat traffic differently by giving preferential treatment to those that pay for it.

Net neutrality in the real world

Being in control of something like the infrastructure of the internet gives you tremendous power. That power is an easy thing to abuse.

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

You, by virtue of reading this editorial, are a user of the internet. You are paying your ISP to relay this content through the internet and to your screen. It's likely your access is tiered in some way. Most hardline connections in the United States are tiered based on the service speed, while most mobile connections are tiered based on the amount of data you can download during the billing period. There is nothing inherently wrong with either method.

Being in control of something like the infrastructure of the internet gives you tremendous power.

This website is also paying for internet access for our servers. We pay our ISP to send our content to their servers. There's a good chance that our ISP and your ISP are not the same company. In that case, ISPs have peering agreements with each other, with traffic flowing freely between them. There's an understanding that there's no need for an exchange of money because the traffic and thus the money would all balance out in the end. Peering agreements are the equivalent of "calling it even". I owe you $50, you owe me $50 — we could swap Grants, or we could just shake and call it even.

But not all peering agreements are working out in this age of streaming media. Take Netflix as an example. Streaming one hour of Netflix at HD quality adds up to a little over 2GB worth of data. That 2GB comes from Netflix's server through Cogent (their ISP) to your ISP through to your screen. The only way things balance out in a fair peering agreement is if your ISP is sending 2GB back through Cogent (but not necessarily to Netflix).

By most measures, Netflix accounts for around a third of US internet traffic. They are by far the largest single source of data downloads, but they don't even register in the top ten for uploads. That should come as no surprise, considering that there's nothing that Netflix users upload to the service other than the basic command that triggers the streaming video in the first place.

So the peering agreement between Cogent and, say, Comcast is out of balance, and it's all Netflix's fault. Even if it means that the cost will be passed on to the consumer, Netflix should pay to make up the difference, right?

If you were expecting me to say "wrong", you are mistaken. It doesn't go against the principles of net neutrality to manage peering agreements that are out of balance. There's nothing inherently wrong about Comcast or Verizon striking agreements with Netflix to help manage the load that the streaming service has put on their internet service. While this means that the cost will eventually be passed on to consumers, it also means that Comcast and Verizon can take that extra money and use it to improve their infrastructure. They know that the customer blames them for a poor Netflix stream.

Infrastructure as a weapon

Where this has gone wrong is how Comcast and Verizon managed to coerce Netflix into the agreements. All three are large, profitable businesses, and in the interests of staying profitable they're all loathe to part with money if they don't have to.

By controlling the infrastructure that connects Netflix to their customers, Comcast, Verizon, and other ISPs hold a strong hand against Netflix. They're able to inflict damage on Netflix, and they possess much more sophisticated public relations and political lobbying mechanisms than Netflix could ever dream of. So they can get away with things like artificially throttling the speed on Netflix streams to customers and publicly blaming Netflix for it. When the customers complain about their Netflix stream quality, the ISP just points to Netflix and says "they're crippling our network!"

With customers uneducated as to how the internet functions and what their ISP is doing with Netflix's traffic, the customer would naturally blame Netflix. We might rank cable companies as the most despised in America, but with the vast majority of us lacking in technical knowledge about how the infrastructure of the internet works, we're willing to take the cable company at their well-produced word.

At the same time, Comcast is providing their own video-on-demand service over the same cables with a similar per-user/hour load, and not placing any restrictions on the bandwidth it has available.

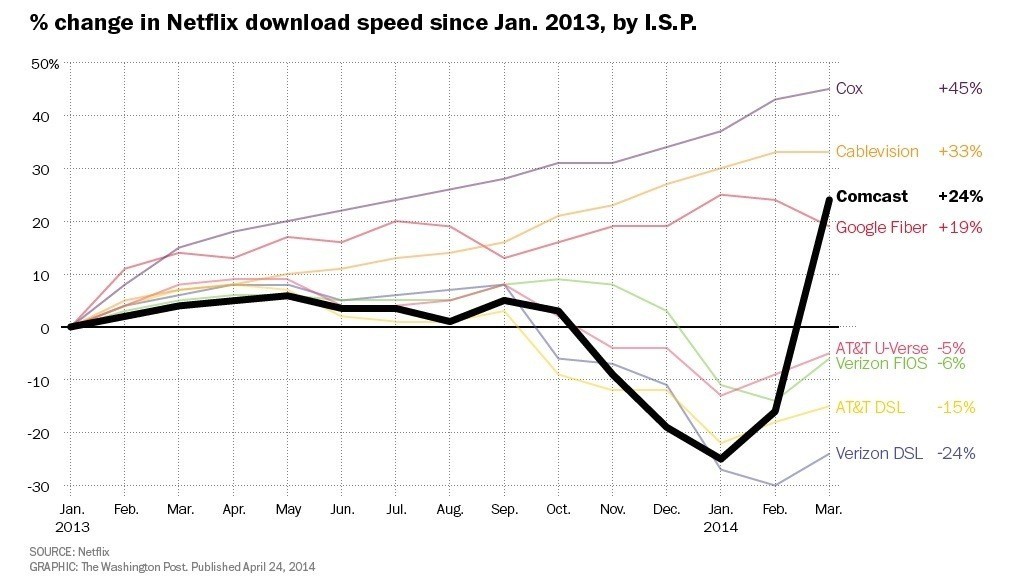

In January of 2014, Netflix agreed to compensate Comcast for the massive traffic load that the video streams placed on their networks, with the interconnection fees beginning to be paid at the end of February. By the middle of April, Comcast customers saw the speed and thus quality of their Netflix streams dramatically improve — by 65%.

It's highly unlikely that Comcast was able to upgrade their infrastructure so substantially as to boost their ranking from second-to-last up to third-best in two months. Netflix payed Comcast's ransom, and they got what they were promised.

Netflix's speeds on Verizon have ticked up slightly since their recently-signed agreement, and it wouldn't be surprising to see a substantial jump there either. Netflix has also stated that they are working on similar agreements with other providers — the chart below assembled by The Washington Post tells you all you need to know about which ISPs Netflix is likely negotiating most intently with.

Woe is the big profitable corporation

Before you accuse me of offering pity to Netflix, I understand that this is a matter of multiple large and highly profitable companies haggling over millions of dollars. It's Netflix, it's purely an entertainment service, and while it's frustrating that the speed that you're paying your ISP for to get that service might not be the speed that you're getting to stream the latest season of House of Cards, that's not the end of the world. So what if Frank Underwood's hair and Claire Underwood's dresses aren't as crisp as they could be? It's just a TV show.

And you're right. It's a pain that you're not getting what you paid for, but that's all it is, a pain. Netflix is entertainment, and entertainment like Netflix is among the most superfluous of human needs. It's nice to have, and it's even nicer when it's better quality, but it's merely padding the quality of our lives.

Cable companies shouldn't be coercing deals by artificially choking their traffic.

"But it's the principle of the thing!" you shout. And yes, you are right. Netflix absolutely should cover their share of the mismatched peering arrangement. But Netflix shouldn't have been coerced into such a deal by having the cable companies put an artificial choke on their traffic. Perhaps that punishment was what was needed to force Netflix into bowing to common sense and picking up their fair share.

But the cable companies went after Netflix because it's a big and visible target, one that we've all heard of and many of us use. Most of us haven't heard of companies like Cogent or Level 3, business ISPs that are responsible for delivering Netflix's traffic to our own ISPs. When Comcast goes after them, we don't notice. In fact, Comcast has already managed to wring extra money out of Level 3 for their Netflix traffic, and they're still trying to do the same with Cogent even though Netflix is paying them directly as well.

It's easy to not care about the plight of corporations like Netflix, Cogent, and Level 3 getting shook down by corporations like Comcast and Verizon. They can afford it, or they can at least afford the lawyers to fight it out. Whatever, right?

Setting a precedent for extortion

Netflix being extorted by ISPs is an isolated incident, at least for now, but it sets a truly bad precedent. Netflix can afford it, and so too will Google when ISPs start actively throttling YouTube streams. Apple can afford to pay to ensure their content is delivered in a timely fashion, and so too can Amazon.

Can the smaller companies just getting up on their feet afford to pay the ransom demands of Comcast? Not likely, but their traffic will be held hostage just the same. This sets a dangerous precedent that will eventually trickle down to smaller and smaller internet content providers: pay up or be throttled. If you can't pay, the service you're attempting to provide will suffer, customers will leave for faster services, your revenue will drop, and you'll never be able to catch up to pay the racket to get your data flowing again.

This sets a dangerous precedent that will eventually trickle down to smaller internet content providers: pay up or be throttled.

And once the ISPs have squeezed all of the money they can out of the content providers, it's all but assured that they'll turn to their customers. "Your streaming of Netflix is putting a huge burden on our overtaxed network," they'll say. "I know you're paying for a fast connection, but if you're going to be streaming content like this, you're going to have to pay an additional fee so we can help build up our infrastructure."

These arrangements severely complicate how the internet works. Instead of Netflix paying their ISP for access to the internet and you paying your ISP for access to the internet, Netflix is now paying their ISP and your ISP for what you are already paying for. And your ISP bill isn't going to go down as a result.

In the last fiscal year, Comcast raked in a very healthy profit of $6.2 billion. To say that they need to be payed off by Netflix to afford to upgrade their network to handle what it is clearly already capable of handling is ludicrous.

Comcast is not alone here. Cox Cable and Comcast have been found to be blocking the use of VPNs (virtual private networks, typically used by businesses so employees can access the corporate network from the outside world) by their residential customers. AT&T has threatened customers using cellular Wi-Fi hotspots as their home network with claims of "theft of service" constituting a federal crime.

That any carrier can discriminate against any packet of data for any reason has great potential to cripple the internet.

In stumbles the FCC

In the United States we have a governmental organization charged with regulating electronic communications: the Federal Communications Commission. It is an independent agency of the federal government, with broad authority over telephones, broadband communications, and the wireless spectrum. The FCC possess substantial power to regulate these industries with the goal of promoting "rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communication services with adequate facilities at reasonable charges."

In short, the FCC's purpose is to ensure that the people and businesses of the United States have the best communications tools at a reasonable cost. The FCC is lead by five commissioners, each appointed by the then President of the United States to serve a five year term. These commissioners are approved by the Senate, and no more than three may be from the same political party and none may have a financial interest in the businesses that the FCC regulates.

From there they are an independent body, supposedly free from political manipulations. Their goal isn't reelection or a higher political office — it's to manage the communications industry of the United States for maximum benefit of its citizens.

And so, with ISPs like Comcast and Verizon extorting content providers like Netflix to pay for the traffic that their customers were already paying for, the FCC stepped in. What was happening here was pushing against those principles of rapid, efficient, and reasonable that the FCC is meant to uphold.

And then the FCC fumbled. Hard. Repeatedly. The FCC fumbled for years in trying to regulate ISPs with a light and guiding touch. With billions in profit at stake and an army of high-dollar corporate attorneys at their back, the ISPs have fought hard against these attempts to ease them into place.

In 2010, the FCC put in place a set of net neutrality rules — the Open Internet Order — that required transparency from and prohibited blocking and discrimination by ISPs. These rules were immediately challenged by those ISPs, and earlier this year we saw the case of Verizon v. FCC in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals end with the blocking and discrimination portions of the Open Internet Order vacated.

Eight years ago the FCC decided on the wrong words to describe ISPs in the eyes of the law.

The reasoning for the court's decision? The FCC's power to enforce such rules only applies to common carriers, and according to the FCC's own rulings, ISPs are not considered to be common carriers. A common carrier is a company that is regulated by the government to provide a service without discrimination. In exchange, these carriers are generally immune from liability for having carried something — you can't sue the phone company for connecting calls between mobsters, for example. Airlines, taxicab companies, and railroads fall under common carrier laws, as do public utilities and most telecommunications providers. Except for internet services providers, that is.

The hiccup in the plan here dates back to 2005, when the FCC classified ISPs as information services and not common carriers. Few at the time had anticipated what the internet would look like eight years from then.

The funny thing is, in some ways the government does treat ISPs like common carriers. Thanks to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, carriers are immune from liability for the content that is distributed over their networks. But thanks to their ability to fund expensive and highly effective lobbying efforts, ISPs have largely avoided the restrictions of common carrier status while reaping the benefits when it suits them.

The FCC's 2005 classification of ISPs as information services meant that their 2010 Open Internet Order was mostly toothless. Because 8 years ago they had decided on the wrong words to describe ISPs in the eyes of the law, the strongest net neutrality provisions they had on the table were swept away.

How do we fix this?

The argument for how to fix this issue is relatively simple: the FCC declares internet service providers to be common carriers. The regulations they had attempted to enact in 2010 would then be applicable and we would all be living in a world of internet free from the pressure for everybody to pay two or three times for the same service.

The appeals court that struck down the FCC's rules even acknowledged this, calling out the technicality in the FCC's rules and not disputing that the FCC had the authority to declare ISPs to be common carriers. No doubt such a move would bring an immediate court challenge and keep those high-priced telco lawyers gainfully employed for years to come.

But in the end this is the FCC's decision to make. They can either keep trying to nudge and ease ISPs to into place with a gentle touch that has so far failed miserably, or they can declare ISPs to be common carriers and step up to the fight.

The FCC can stand up for what's right.

We believe in the power of capitalism, but also in sensible regulation. We believe that all web traffic should be treated equally, be it reading scholarly articles on quantum mechanics, watching House of Cards on Netflix, or participating in the communities here on Mobile Nations. We believe that access to information should not be restricted merely because there is a lot of it. We believe that fair access to the internet and everything on the web is all but essential for success in this age, and that limiting that access will impede not just the users of the internet, but the nation as a whole.

Net neutrality isn't just about who should pay for the bandwidth that a streaming show on Netflix uses. Net neutrality is about equal access to everything the internet has to offer, for the benefit of the citizens of the United States and the rest of the world.

Fair access to the internet and everything on the web is all but essential for success in this age. Limiting that access impedes the entire nation.

Right now there's a petition going around on the White House's We The People platform calling on the administration of President Obama to reclassify ISPs as common carriers. Such a petition is a toothless measure, and not just because it's a non-binding petition (We The People only requires that the administration issue a written response to the petitioners — and those responses have included petitions to build a Death Star and deport Justin Bieber, both worthy movements).

Earlier we mentioned that the FCC is an independent agency of the United States government. Its commissioners are appointed by the President and approved by Congress, and like anybody they can be dragged before Congress for hearings, but they operate independently of the rest of the government per their chartering by the Communications Act of 1934. Of course, that doesn't mean they're immune from pressuring by Congress, the White House, or telecom lobbyists. It also doesn't mean they're immune from pressuring by you.

A White House petition will do little good (we aren't even going to bother linking to it here). President Obama has twice campaigned on a platform that included net neutrality, so his administration's position on the issue is clear. He has appointed FCC commissioners that he felt would best uphold his goals for the FCC. They may have fumbled so far in doing that, but they still can get their act together before it's too late for the internet.

If you want to express your desire for a free and open internet, there is something you can do: tell the FCC.

Tell the FCC to do what is right

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has said that he "won't hesitate" to declare ISPs common carriers in order to ensure that the "the 'next Google' or the 'next Amazon' is [not] delayed or deterred", but we are fast approaching the point where we will be too far down the rabbit hole to reverse course and declare ISPs to be common carriers.

The declaration of common carrier status for ISPs has to come now. More talking, more threats, and more negotiating won't solve the problem here. Definitive and decisive action is what is needed to ensure that access to the internet remains free and open to all.

We are calling on the FCC to declare internet service providers to be common carriers and to apply applicable regulations to ensure the principles of net neutrality are upheld. The future of the internet depends on it. The future of the United States of America depends on it. Do not let the information access of the people of this nation be held captive by corporate greed.

We urge you to contact the FCC yourself to ensure that your voice is heard by the commissioners.

Chairman Tom Wheeler:

Commissioner Mignon Clyburn:

- Mignon.Clyburn@fcc.gov

- @MClyburnFCC

Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel:

Commissioner Ajit Pai:

Commissioner Michael O'Rielly:

Contact the FCC:

- openinternet@fcc.gov

- File a complaint

- @FCC

- Call: 1-888-225-5322

- Federal Communications Commission

445 12th Street, SW

Washington, DC 20554

Net neutrality is worth fighting for

We're talking about the future of the internet as a free and open information platform for everybody on the planet.

Net neutrality is the right thing to stand up for. Our ISPs are beholden to their shareholders and maximizing value for them. There's nothing wrong with that. The FCC is beholden to us, the people whose rights it was created to protect. Remind them of that.

Derek Kessler is Special Projects Manager for Mobile Nations. He's been writing about tech since 2009, has far more phones than is considered humane, still carries a torch for Palm (the old one), and got a Tesla because it was the biggest gadget he could find. You can follow him on Twitter at @derekakessler.