Your phone has data that can help track coronavirus cases, but should it be shared?

An event like the COVID-19 outbreak shows just what can be done with data collection. The same data collection that was happening before the pandemic.

Right now that's easier to see than ever as data collection and processing companies have found ways to track the movement of the Coronavirus by tracking our movements, and then making the data public for the world to use. It's anonymized for the most part, but it doesn't have to be and it's a little scary to see just how companies in the business of tracking us do it so well.

Coronavirus and tech: Ongoing list of event cancellations, disruptions, product delays, and more

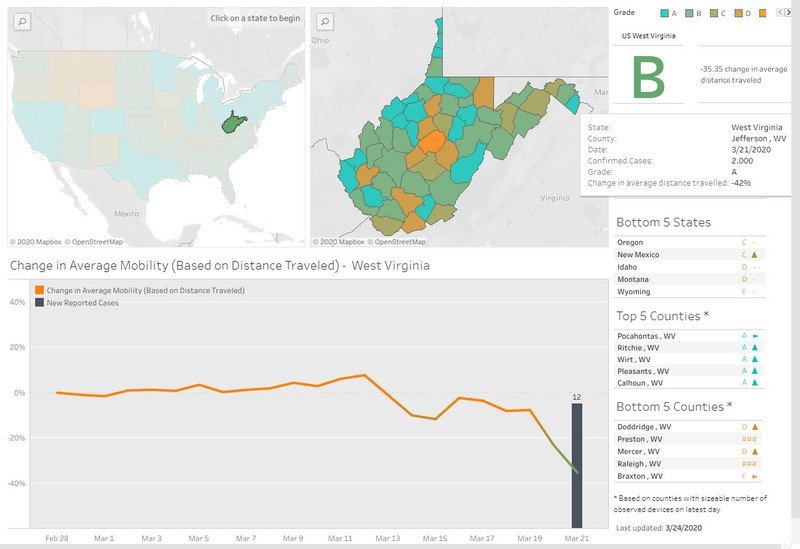

A company called Unacast is building a COVID-19 Toolkit using data directly from your phone and it serves as a chilling example of what can be done with the information we probably didn't even know was being uploaded. Using your find location history that's been gathered from other apps, the way we're moving around — or not moving around — is displayed in a nice interactive presentation that's accurate down to the individual county level.

Unacast partners with other app developers to collect your location data on both Android and iOS. What it's doing isn't illegal by any means, as you consented to the location usage when you first installed or ran the application. Unacast just collects what we give freely.

See the Social Distancing Scoreboard here

And that's not the most disturbing thing we've seen in the past week. A company called LogoGrab was able to parse public Instagram photos and videos and match them to the location they were taken so the Italian government could track how many people weren't following quarantine orders. 552,000 Instagram users were profiled during the period of March 11 to March 18 and it turns out that about 40% of Italy's Instagram users aren't conforming to shelter-in-place orders.

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Location can easily be attached to a face when AI enters the picture.

This data is helpful. We know it is because of countries like Singapore or South Korea that used location-tracking apps to monitor an infected person's past travels so warnings could be sent. It's also worrisome because Taiwan uses this data to identify persons who may have been exposed and have strayed outside of their allowed lockdown range, then contacting them with a message to call the police or face a $33,000 fine.

In the United States, the government can not force a company to release any of the data it has collected without a warrant. But that doesn't mean it can't ask nicely: Google and Facebook have both been contacted about using aggregated location data to fight the virus. Google says it has not shared any data with the government but is considering it.

Collecting this data is nothing new, but seeing it laid out this way is and exposes the need for better data protections for all.

This data has always been collected, but the recent pandemic exposes it in a nice and easy to use package. Most companies involved are trying to assist for the greater good, but it does force us to consider the question of what else corporations and governments are doing with our data.

Maybe it's time to rethink how data is classified and left unprotected. If credit reporting agencies and doctors are bound by certain rules when it comes to personal and private data, shouldn't location scrapers who pay to grab data from a popular game have rules to follow as well?

Once the current crisis is over and done, I hope someone has the gumption to have a long hard look at how our data is handled and what changes need to be made.

Jerry is an amateur woodworker and struggling shade tree mechanic. There's nothing he can't take apart, but many things he can't reassemble. You'll find him writing and speaking his loud opinion on Android Central and occasionally on Threads.