Racing to the app grave: the dead, the zombies, and the parasites - Talk Mobile

Presented by Blackberry

Talk Mobile Gaming

Racing to the app grave: the dead, the zombies, and the parasites

Your finger hovers over the download button in the app store. Maybe it's free, maybe it's not. Even if it's only 99 cents, you spend four times that at Starbucks every day. Yet you hesitate, haunted by memories of that app you downloaded a few years ago, fell in love with, and then watched as the servers shut down and the app was abandoned and left to wither and die on your launcher.

Apart from finding an app that suits our needs, we're now left to wonder if the app itself will even last a few months, much less years.

That can make us hesitant to hand over money, even a mere dollar, for apps that a developer spent months, if not years, building. It makes us consider if paying up front for apps and services is the best way, or if we can minimize risks by going with free-as-in-ad-supported or in-app-purchase-financed apps instead in hopes that maybe that will help keep them around.

It makes us wonder -- can we depend on our apps? Can we count on them to be there for us when we need them? How do we know?

Get the latest news from Android Central, your trusted companion in the world of Android

Let's get the conversation started!

By Daniel Rubino, Kevin Michaluk, Phil Nickinson & Rene Ritchie

Play

Depending on apps

Articles navigation

- Apps that stay

- Video: Guy English

- Race to the bottom

- The cost of free

- Apps that die

- Video: Dieter Bohn

- Conclusion

- Comments

- To top

Rene Ritchie iMore

Sometimes good apps die, and that's okay

Then it goes away.

It gets bought out, goes out of business, gets shut down, or just plain disappears.

We may feel like we own our apps and services, but we have zero real control, and getting reminded of that sucks. Hard.

Throwing services at the wall

Google has long had a rap for killing off products that failed to live up to expectations or have outlived their usefulness. These "spring cleanings" have taken down products like the Google Wave collaborative workspace and the failed Google Buzz social network, as well as niche products like Google Reader and promising initiatives like Google Health.

Apple's iTools launched in the early days of the internet in 2000. It was followed in 2002 by .Mac and in 2008 by MobileMe, which struggled with stability and availability. A replacement came in 2011 with iCloud, which aims to serve more as a cloud conduit between devices. Apple tried their hand a social network with the music-focused Ping built into iTunes in 2010. By 2012, Ping was quietly shuttered after failing to catch on.

Some of the biggest companies on the planet have killed some of the best services.

So what can we do, when we find a new app, an app we think we'll love, to make sure we don't get our hearts broken?

Sadly, very little. Some of the biggest companies on the planet have killed some of the best services. Apple has killed everything from iDisk to Ping (hey, someone must have loved it!). Google's killed so many apps and services I've lost count, though Google Reader is one of the most recent and most hurtful.

Having a business model doesn't hurt. Everyone needs to make money to survive and free apps can't stay free forever if they expect to last. Charging real money for real apps and services is no guarantee -- stores are filled with the abandonware corpses of apps that just couldn't make enough to keep going, even when fairly priced.

If you're getting something for free, and you're not giving anyone any money, chances are eventually they're going to need money.

- Guy English, Host of Debug, App Developer

At the end of the day, the only way to trust that the apps and services you depend on will stick around is to not trust that the apps you depend on will stick around. That means picking apps where you can easily export your data and your content and store it in a standards-based, or at least widely-supported format.

You can't ever tell if an app or service you love will one day leave you. All you can do is make sure it can't take all your stuff with it when it goes.

Q:

Can we depend on our apps?

1313

Kevin Michaluk CrackBerry

Since when was $0.99 considered 'expensive'?

There's a reason people won't pay for apps? Apple. Seriously. And it pisses me off. Contrary to popular belief, Apple didn't invent apps on mobile devices. Many of us bought software for Palm OS and BlackBerry devices for years before Apple launched their App Store. And we used to pay for them. A lot. Palm and BlackBerry software would sell for $24.99 in the mid-2000's and we paid it without complaint. We saw the value, similar to console gaming.

Then came the App Store, the race to the bottom, and the commoditization of mobile software.

Not wanting to pay a lot, or pay at all, for content isn't something unique to mobile, of course. Software piracy, like video piracy, is the most extreme example, and it's been prevalent for years. If people can find a free way to obtain expensive software, movies, etc, many will, despite any legal or moral arguments against it.

So, when people can legally and morally get free or super-cheap software, of course they jump at the chance.

People become unwilling to pay, developers race to the bottom, and here we are.

Economies of scale

In the waning days of Palm OS, the PDA and smartphone pioneer struggled to compete with the popular iPhone and Android smartphones. The app situation on Palm Treo smartphones didn't help: the premier document-editing suite for Palm OS - Documents To Go - cost $49.95. There wasn't yet a comparable app for iPhone or Android, but the price tag was hard to stomach for many.

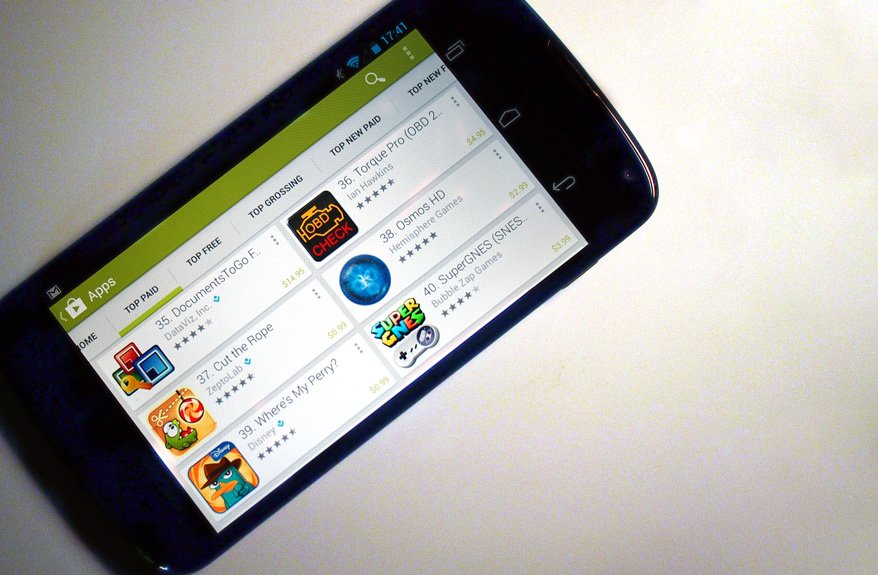

Early apps in the iPhone App Store weren't priced as they are today; they mimicked the pricing from Palm OS and BlackBerry. It didn't take developers long to see that the iPhone was a different beast, with significantly more potential customers. Economies of scale kicked in when developers began to discount their apps in order to sell more at a lower profit margin. Today it's rare to find an app that's priced above $5 in a modern app store.

Apple as the first, and app stores that have followed, set the expectation that mobile apps aren't worth very much. People become unwilling to pay, developers race to the bottom, and here we are today with stores filled with 99-cent apps.

Once you get down to 99 cents per app, why not free? No piracy, no barrier to entry, and if there's no real business model, who cares, right?

Google Play has a reputation for being the place to go for those who really don't want to buy apps. Open or closed, it doesn't really matter when the apps are free or nearly so.

I'm the opposite. I want to pay for apps. My time is more valuable than money. When I'm looking for apps, I don't want to waste a second on the free or cheap alternatives -- I go directly to the most expensive one available, expecting it will also be the best made and most feature-rich app available. It's not always the case, but it's often enough the case.

More importantly, it supports developers and promotes more paid apps. And that's what I want.

Q:

Has the commoditization of apps affected app quality?

1212

Daniel Rubino Windows Phone Central

Free apps now, though you'll pay later

Whenever I hear of a new free app or game, two things come to mind: ads or freemium. That is, most apps and games worth their salt aren't free without those hindrances - even major services like Facebook and Twitter integrate advertizing.

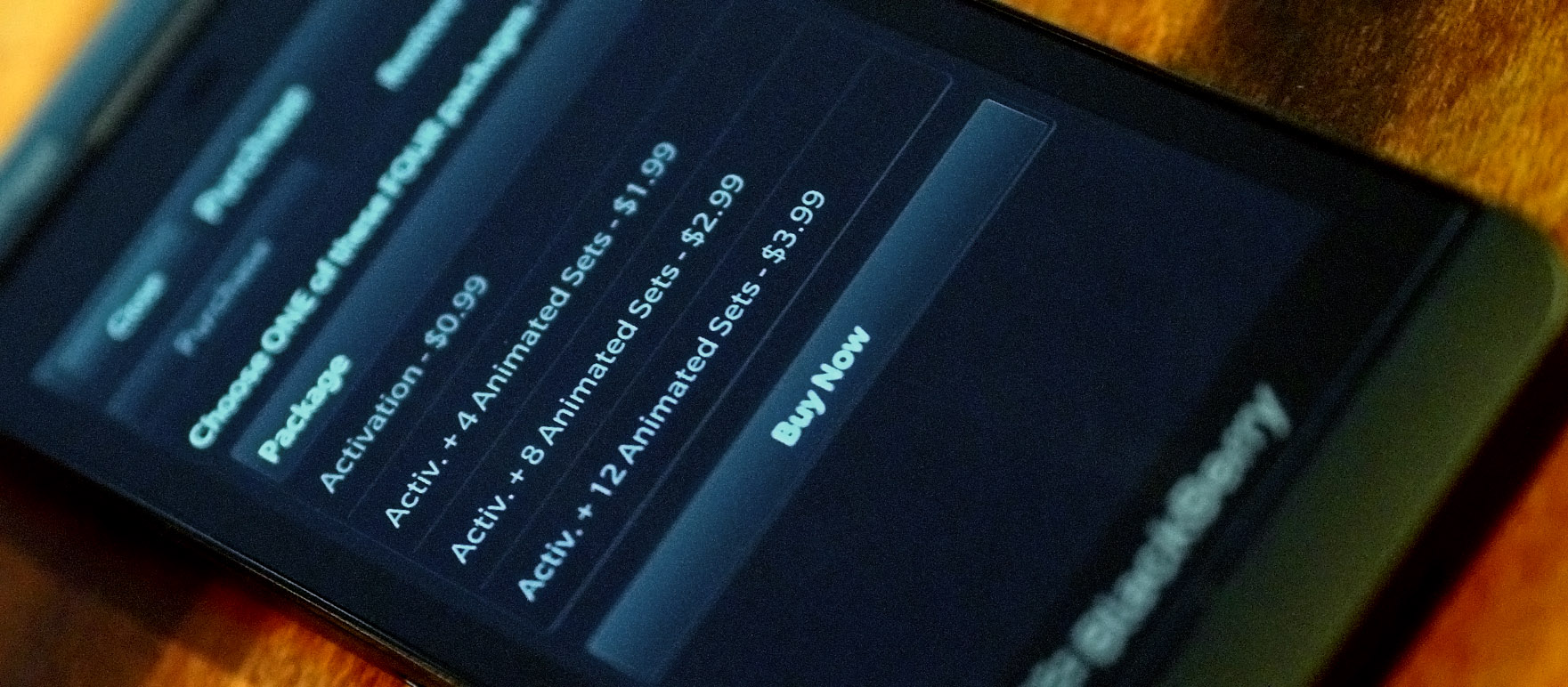

Ad-supported freeware apps or pay-as-you-go games are either the best things to happen to mobile apps or the worst thing ever. One perspective is that a free app or game that relies on in-app advertising will use more battery, thanks to it having to download up-to-date geo-targeted ads to display. Such periodic retrievals, combined with your constantly being presented with advertising that's designed to distract your attention, worsen your overall smartphone experience.

Are in-app purchases worth it? Are they a bad thing?

The same can be said of free games that have optional pay-as-you-go extras that enhance the game's experience, or free apps that are severely feature limited and pester users for upgrades. While 99 cents here and 99 cents there may not seem like much, if you do that over days, weeks and months, you could end up paying $20 or more for a single app instead of just a few bucks up front. Are in-app purchases worth it? Are they a bad thing?

One other area of concern regarding "the cost" of free apps is in design. When making an app or game, the developer must now include an area where the ads can reside, often interfering with the overall design aesthetic of the project. Once again, while some people may not be bothered by such considerations, others - myself included - find it less than appealing.

Charge it to the battery

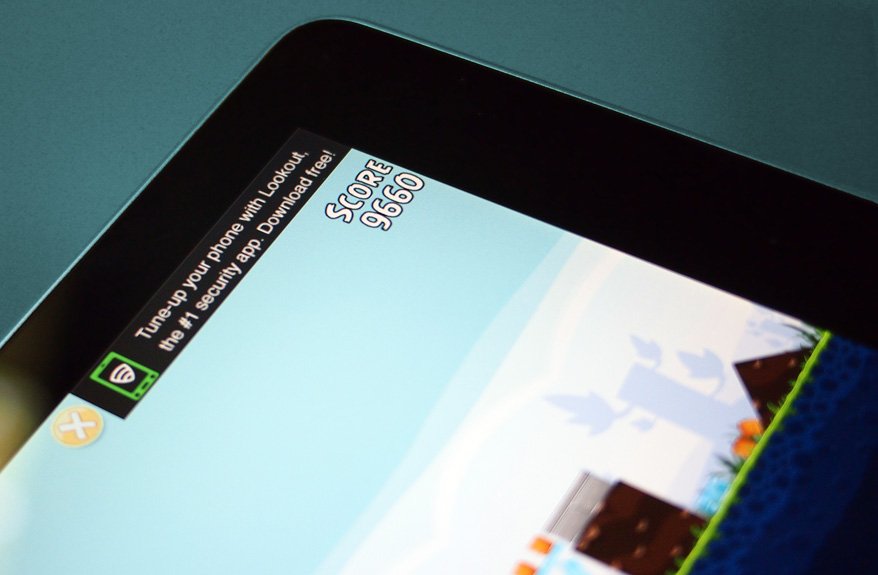

Free apps that are supported by in-app advertising have to get that advertising from somewhere. But how much does that cost you? In terms of battery charge, it can be substantial. A Purdue University computer science PhD candidate in 2012 calculated that for the free ad-supported version of Angry Birds released for Android nearly half of the battery usage was spend in support of advertising.

The analysis found that just 20% of the battery use came from running the game and display. Determining the player's location by GPS and downloading location-targeted ads over 3G amounted to 45% of the battery usage, while nearly 30% was spent on latent data connections that persisted even after the ads had been download.

As a point of comparison, the Angry Birds game series is available on every major platform. On the iPhone you can pay a dollar upfront for the original Angry Birds, or you can download the free version and deal with the ads. Rovio experimented with the ad-supported version first on Android; within three months of the launch in October 2010, Rovio was projecting advertising-driven revenue of more than a million dollars per month. Since then, Rovio has gradually taken to offering their games in free ad-supported and paid ad-free versions on most platforms.

The only right answer here if a developer wants to hit the broadest audience possible is to give the consumer a choice: a paid, non-ad-supported version and a free, ad-based alternative of the app. Besides the development time, which is often nominal, this would appear to be the best route to ensure the greatest customer satisfaction and larger financial returns to the developer.

Q:

Are free ad-supported apps worth the cost?

313

Phil Nickinson Android Central

Where one app dies, another rises

Most of us don't have nightmares of our favorite app one day disappearing, but it has happened before, and it will happen again. Nobody expects Angry Birds to die without warning, but more subtle disappearing acts will continue as time goes on.

The thing to remember is that apps may come and go -- but it's the services that are really important. Take, for instance, the heralded Sparrow app for iOS, an anticipated and beloved Gmail-specialized app. Google purchased Sparrow in 2012 and largely has left the app to die on the vine. But at the same time, Google's own Gmail iOS app has been greatly improved in more recent versions, adopting some of the interface schemes of Sparrow. One app dies, another is resurrected.

One app dies, another is resurrected.

Twitter's terms

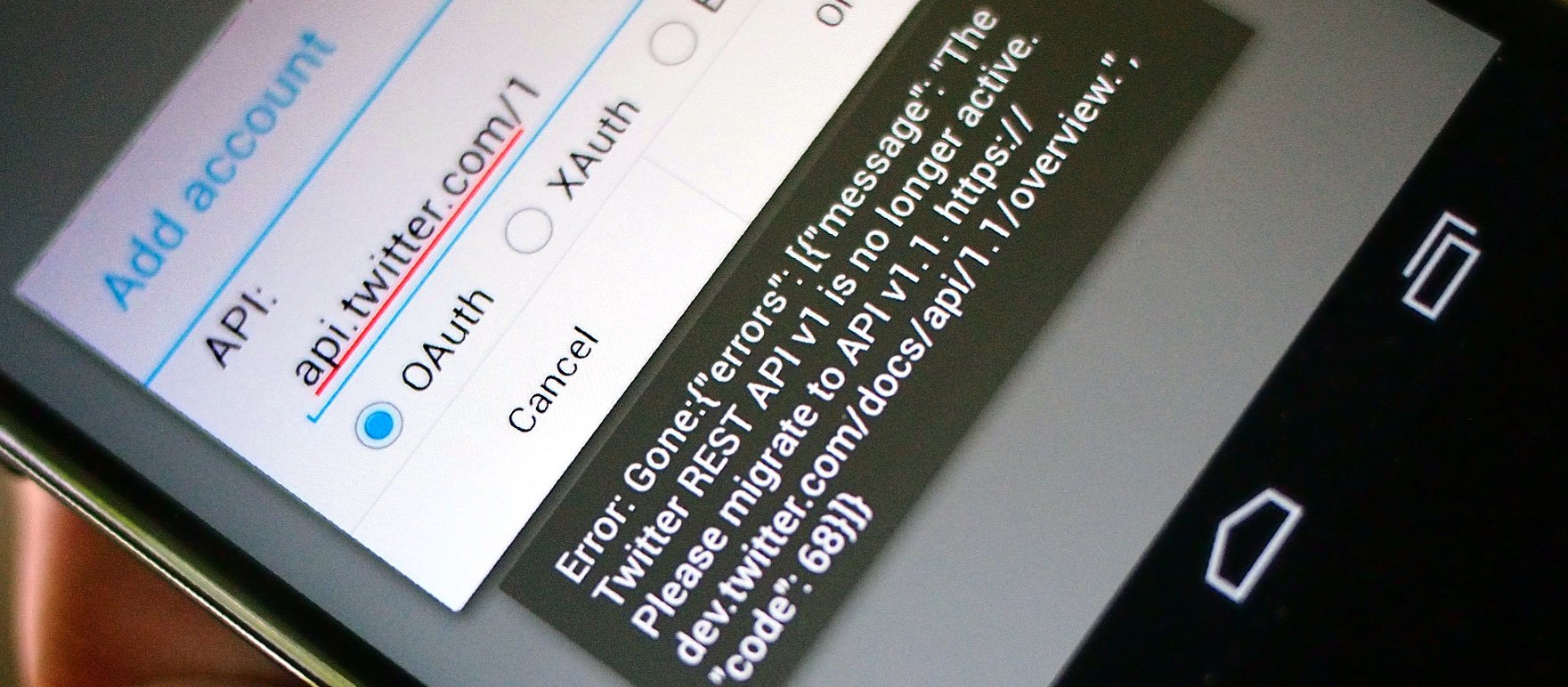

In August 2012, Twitter announced the new v1.1 Twitter API, requiring log-in authentication and limiting the number of user tokens for apps. New apps under v1.1 were limited to 100,000 users, while existing apps with more than that would be permitted to double their users before hitting the cap. Twitter also began dictating how content could be displayed in apps.

The 100,000 user ceiling proved to be a controversial change. While Twitter said they could give permission to exceed the 100,000 token limit, no known app has been granted such an exemption. Popular apps like Tweet Lanes, Tweetro, and Falcon Pro quickly bumped up against the limit and are exploring new ways to allow new customers to use their apps. Tapbots took a different route with their release of Tweetbot for Mac, pricing it at $19.99 so they could net a healthy profit before hitting the imposed ceiling.

Today, Twitter apps are a dime a dozen. For a long time it was fairly easy for anyone to crank one out. But Twitter has begun clamping down on the use of its APIs, putting a hard limit on the number of users any one API key can have - new apps are limited to a paltry 100,000 users. Popular rising Twitter stars like Falcon Pro on Android have already bumped up against that limit in just the short time its been in place. And we've already seen a number of developers get off the Twitter train, leaving behind (or at least releasing into the open-source community) excellent applications. Twitter has begun to improve its official app, but there's very much a bad taste in a lot of mouths over this one.

As Rene said, the only way to trust that the apps and services you depend on will stick around is not to trust that the apps you depend on will stick around. We live in a rapidly advancing digital world, and in that frenetic pace apps and services are going to be left behind. Sometimes they can't keep up, sometimes they're abandoned, and sometimes a developer just builds something better. Change can hurt sometimes, but it has to happen for technology to advance.

I've had a few of the apps that I depend on go away. You try to find a replacement if you can, and if you can't you just have to grin and bear it.

- Dieter Bohn, Senior Mobile Editor, The Verge

Q:

Talk Mobile Survey: The state of mobile apps

Conclusion

There's never any guarantee that the app you download today is going to work tomorrow. The app might not disappear off of your phone, but that cloud service it depends on go offline, or the app might stagnate without receiving updates to make sure it stays relevant in a quickly-advancing world.

The only constant we can count on is change. Apps will be abandoned, developers will be purchased, services will shutter, and competitors will rise from nothingness to tromp all over everything that was there before. It's the nature of technology, and while it sometimes wreaks chaos on our routines, the end result is usually an improvement. Modern smartphones rose up and demolished the old order; some of the old guard was able to make the transition, others were left behind.

Apps going the way of the dodo is something we have to accept. It's going to happen, and it might even happen to an app you bought and love. But knowing that it could happen, that it will happen, should be enough to prepare us for that eventuality. And then it's back into the application store to find a replacement.